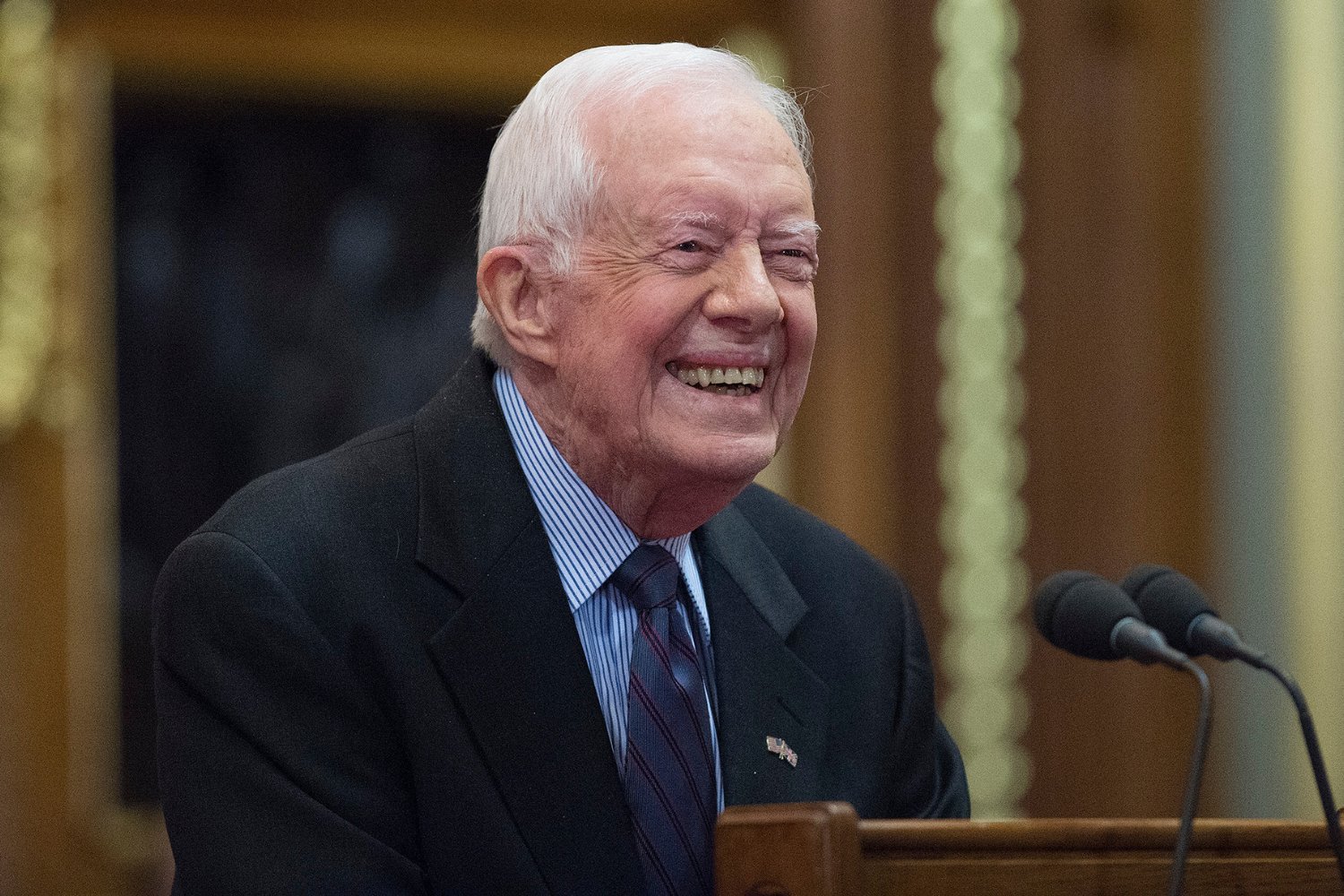

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter is dead at the age of 100. While there are many aspects of Carter’s life that deserve spotlights, few might be as noteworthy as his efforts to help wipe out one of the world’s most horrific parasites, the Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis).

Carter died at his home in Plains, Georgia on Sunday, nearly two years after he first began hospice care. Though he only served a single, often much criticized, term as the 39th president of the United States, his accomplishments extended well beyond those four years. Chief among those successes is the Carter Center’s Guinea Worm Eradication program, which is now inches away from total victory.

Guinea worm is a parasite with such longstanding notoriety that it’s referenced in the Old Testament. The freshwater nematode typically infects people through the consumption of drinking water that contains copepods—tiny crustaceans—which are themselves infected with worm larvae.

The larvae reach our intestines, where they fully mature and mate. The males then die and the pregnant females—which grow up to three feet (100 centimeters) long—migrate to a spot underneath our skin, usually along our legs. About a year after infection, the females cause a blister to form. When this blister breaks, the worm slowly emerges from our skin, triggering a painful burning sensation that drives the infected to cool their wound off in the nearest water source. The female then releases thousands of larvae into the water, restarting the whole process.

This infection isn’t just unpleasant to suffer—it’s often downright debilitating. The worm can take days or weeks to safely and painfully extract, during which time people are unable to work or go to school. And if the worm breaks off during removal, it can trigger secondary infections that eventually lead to permanent disability.

While freshwater sanitation made Guinea worm disease less of a global issue by the late 20th century, about 3.5 million people still contracted these infections annually across Africa and Asia during the 1980s. In 1986, Carter’s non-profit organization, the Carter Center, began a public health campaign to eradicate the guinea worm. And it’s been a clear success. Last year, there were just 14 cases of reported Guinea worm cases in humans; as of November, there were only 7 cases in 2024.

Carter and his organization don’t deserve all the credit, of course. The World Health Organization and other large groups have also played a significant role, while community leaders and residents in endemic areas are the driving force behind eradication efforts on the ground. Since there is no vaccine or drug for Guinea worm, the eradication campaign has largely relied on physical interventions like durable straws that filter out infected copepods from drinking water, as well as meticulous surveillance of potential cases.

Not everything has gone smoothly for the campaign. The Guinea worm was a suitable candidate for eradication because the worms primarily rely on human hosts to reach their full life cycle. For a long time, we thought that only humans could act as this final link in the chain, but it became apparent a decade ago that the species can also mature inside other animals, particularly dogs. So while yearly human cases have remained low in recent years, there have been thousands of reported annual infections in animals over the past decade.

This latest development has impeded the Guinea worm eradication timeline. Until infections in both people and animals reach zero and stay at zero for several years, the worm could persist. But health officials and communities in endemic areas are adapting. Annual reported animal cases recently dipped from 886 cases in 2023 to 448 so far this year, an indication that efforts on the ground are mitigating spread of the parasite among animal hosts.

Jimmy Carter said in 2015 that he hoped to see the Guinea worm completely eradicated before his death. Sadly, that didn’t happen. But Carter certainly has left behind a monumental public health legacy that will endure long after his passing.